ISSN 0976-0911 | E-ISSN 2249-8818

DOI: 10.15655/mw/2021/v12i2/160155

Framing Theory Application in Public Relations:

The Lack of Dynamic Framing Analysis in Competitive Context

Duan Kuan, Nurul Ain Mohd Hasan, Julia Wirza Mohd Zawawi, & Zulhamri Abdullah

Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Received: 4 September 2020| Accepted: 20 April 2021|Published: 4 May 2021

Abstract

This study reviews the literature that uses Framing theory in recent international public relations studies. It aims to overview the research status of Framing theory in public relations and the highlighted core knowledge and voids from scholarly literature. The method used in this study is a systematic literature review, which involves pre-set criteria in selecting academic articles to be surveyed within ten years (1 January 2010 to 31 December 2019) and qualitative synthesis of the findings. A systematic search was conducted related to framing, Framing theory, and international public relations in three databases namely Web of Science, ProQuest Central, and Scopus. These databases contain literature with framing applications in public relations. The main findings reveal that Framing theory was applied with dynamic framing analysis in PR is still weak.

Keywords: Framing theory, taxonomy, systematic literature review, public relations

Introduction

The origin of Framing theory has two orientations, one in psychology, the other in sociology (Scheufele, 1999). Framing research was conducted in the psychology area, usually with cognitive psychology (Gonzalez et al., 2005). Psychology scholars believe that the frame is the cognitive structure of memory. Sociologists believe that the world is complex, and to understand the causal relationship between things, individuals often use the “subject frame” to perceive the world (Sarantakos, 1998). Later, Framing theory became increasingly popular in mass communication and more prominently conducted in qualitative research. Framing theory is combined with communication science to emphasize that framing is to select certain aspects of the facts and make the part chosen more prominent in the communication context (Entman, 1993). Some scholars believe framing analysis is neither a fully developed theoretical paradigm nor a coherent research method (Scheufele, 2004). The research and exploration in many aspects of the theory can be explored and developed. Therefore, it is meaningful to discuss the development and application of Framing theory in different subject areas.

For a long time, Framing theory research has been popular in mass communication. It is widely used in mass communication and the field of public relations (Scheufele, 2004). In mass communication research, scholars focused on how different frames can affect audiences’ sentiments, attitudes, and behavior. These studies pay more attention to the differences in framing effects than on the impact of multiple frame conditions.

In general, numerous competing frames of research have not been entirely explored. For the public relations area, it is the practice of intentionally managing the dissemination of information between an individual or organization and the public and a process of information dissemination and information exchange between the organization, as the subject and the public, as the object. Because of the complexity of overseeing and engaging with many stakeholders in public relations, the essence of public relations is multi-faceted and multi-perspectives. Based on this research reality, framing application in public relations can provide a more significant exploration space for theory advancement. Framing in public relations is a process used by the media and publicists to have a specific message perceived a certain way. In the framing analysis of public relations research, for capturing what occurs in public relations activities, the organization’s frame, as opposed to the media frame, is often compared together.Then the similarities and differences between the organizational frame and the media frame and their impact on the public frame are examined. Chong and Druckman (2007) point out, “little is known about the dynamics of framing in competitive contexts.” As a research paradigm, Framing theory is a family of approaches to diverse texts, which are often common in a communication context. This approach theoretically renders a fresh perspective in various areas of social science studies.

However, it has not yet been determined whether Framing theory has been given due attention and applied in public relations studies because of the discipline’s cross-subject nature. The extent of how Framing theory has reached current work in public relations is also unclear thus far. Lim and Jones (2010) summed up the framing research in public relations from 1999 to 2009. This is the conclusion of the scholars’ summary of the papers on “framing research in public relations” published between 1999 and 2009. Although scholars have identified certain studies with problems, it is impossible to fully grasp the problem’s extent without a systematic examination of the literature. This paper will make a systematic literature review on the application of Framing theory in public relations in the recent ten years to explore new theoretical application trends. Reviewing past literature helps to learn the trends in this area and determine which studies scholars need to design next. This study systematically summarizes the Framing theory application in public relations in the recent ten years to answer the following questions.

(i) To what extent does Framing theory influence current public relations?

(ii) In public relations research, how is the frame competition promoted and influenced by the public?

(iii) What are the application trends of Framing theory in the recent decade of public relations research?

If there is no systematic review of the relevant studies, it is almost impossible to learn the status quo of Framing theory in public relations. This study systematically summarizes the Framing theory application in public relations in the recent ten years to answer these questions. The findings will contribute to refining the framing research paradigm in public relations and provide a guide for the future. This analysis aims to explain where the framing research is focused and identify areas of concern. Therefore, a complete, rigorous, and comprehensive overview of the present studies cannot be extrapolated from a smaller group of samples or sampling influenced by the researchers’ subjectivity. Traditionally, literature reviews are conducted by selecting materials mostly based on the researcher’s subjectivity. The identification or analysis of landmark or classic literature relies heavily on the researcher’s understanding (Vilma, 2015). Therefore, to maintain objectivity in research, this study adopted a systematic literature review with pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria to fully evaluate research on framing analysis in public relations within the last ten years (2010-2019) and analyzed these studies to draw findings concerning the above three research questions.

Literature Review

Framing Theory in Mass Communication

This paper will begin this section by discussing what is framing. Framing theory originated in psychology, developed in sociology, and thrived in mass communication (Appelman & Asmara, 2018). Definitions of the frame can be broadly divided into four categories. The first category is represented by the definitions given by Hertog and Mcleod (2001). They argue that the frame is a product of social, political, and economic context. People interact daily with influential organizations and institutions, which forces individuals, groups, and organizations to adopt certain beliefs and behaviors, whereby the second category is represented by Gitlin (2003). He proposed framing as a constant cognitive, interpretive, and declarative frame and a stable paradigm of choice, emphasis, and omission. This paradigm is a journalistic routine according to which journalists produce news (Gamson, 1992), representing the third category. He believes that the frame’s definition can be divided into two levels—boundary and building frame. The news frame has two levels of meaning—the first is news text choice, and the second is its construction.

Regarded as a theoretical paradigm in mass communication, Framing theory has attracted people’s attention and was considered as the second level of agenda-setting theory. Both theories study how news media draw public attention to news issues. That’s how they set an agenda. But agenda setting deals mainly with the frequency of a topic covered by the media, but it does not discuss how it is treated. Framing takes a further step in explaining how the issue is presented, and it proposes that the media focuses on specific events and then places them within a field of meaning. The Framing theory was then gradually separated from agenda-setting theory.

Framing Theory in Public Relations

There are two types of conceptualization of frame. They are the communication frame and audience frame (Bartholomé et al., 2017). These two frames provide a benchmark for analyzing how public relations scholars understand the nature of the frame. Most framing studies in public relations literature examine one-sided frames or double frames. However, more recent research has examined the one-sided frames of corporations (Anderson, 2018). The initial research on framing focused on cognitive processing at the individual or micro level; the theoretical emphasis on consumers, not just producers, messages are missing from much of the framing literature in public relations (Borah, 2011). The field has an abundance of framing studies. Still, few of them examined the various facts necessary to contruct and negotiate to mean. This type of research cannot tell us whether an original frame could survive the strategic response of adversaries (Scheufele, 2004). Based on this research reality, some public relations scholars started to conduct dual-framing, in which they focus on news coverage of a group’s frame. These studies recognize time as an important variable in framing, like most other framing studies in the past. Subsequently, more studies investigate the impact of competing messages over time and explore the impact of these frames on the public.

Consequently, counter-framing research came into public relations scholar’s sight. Adding counter-framing to the study allows a better way for public relations scholars to examine the democratic environment and helps practitioners use frames strategically, especially in political public relations (Loan, 2020). While more reseachers realized that sponsored-framing research should be more central to framing research, more research should be conducted to explore how influential are sponsors in the interplaying between frames and discourse (Nelson, 2019).

Systematic Literature Review

Systematic literature reviews were first and primarily implemented in healthcare interventions (Eden, 2011). The method aims to provide a comprehensive overview of current literature relevant to specific research questions and provide a synthesis of the findings (Wang et al., 2020). It is distinguished from traditional literature reviews by being objective, systematic, transparent, and replicable (Siddaway et al., 2019). Its origin dates to the end of the 20th century when Mulrow (1987) provided detailed guidelines for carrying out systematic literature reviews in medical studies (Durach et al., 2017). In recent years, it has been applied in fields such as social work or business management in addition to medical or biological studies (Sahni & Sinha, 2016). However, because of the idiosyncrasies of each field, the retrieval, selection, and synthesis of relevant literature in the present process of systematic literature review designed for medical and biological studies need to be adjusted to fit new fields (Durach et al., 2017).

To conduct a systematic literature review, four steps should be taken. First, clear and specific research questions must be proposed. Second, the databases must be clearly defined under the guidance of well-structured questions, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria must be pre-specified (Siddaway et al., 2019). Third, a thorough search for relevant research must be performed with minimal bias. Finally, all samples must be checked according to the pre-determined criteria for findings relating to the research questions (Eden, 2011). To maintain minimal bias, samples are taken from a significant database as well as several supplementary databases. At least two abstractors should do the screening of these samples to avoid subjectivity in reviewing.

Quantitative syntheses were excluded in the review because quantitative syntheses are based on a meta-analysis, which is more suitable for identifying common effects or reasons for variations (Higgins et al., 2019). For example, a meta-analysis could be used to test the effects of new drugs in a pharmacy to check whether a single case is consistent with others. As the Framing theory application in public relations studies is examined with no effect, the review focuses on the research status descriptions. In this case, meta-analyses of quantitative measurement are not appropriate here, and a qualitative synthesis as the last phase of the flow is preferred.

Methodology

The keywords in this work are “Framing theory and its application in public relations.” This keyword includes any words related to “framing.” For instance, “Framing theory,” “framing research,” and “framing analyses.” At the same time, we limited our scope of English literature. Because of the bibliographic databases’ availability and coverage, three databases were selected to retrieve eligible literature for this study: Web of Science, Proquest Central, and Scopus. Web of Science served as the primary database, while ProQuest Central and Scopus were used as a supplementary database. These target articles were selected from digital databases. Proquest Central is the largest multidisciplinary database. Web of Science (WoS) is a comprehensive academic information resource, offering indexing in sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities. Scopus is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature, which may guarantee us a more thorough search of peer-reviewed literature. These databases fully contain Framing theory and its application in public relations. Google Scholar and IEEE are two popular databases that were not included in this review. According to rigorous literature research, Google Scholar lacks ‘advanced search features,’ which renders it difficult, launching a screening process of abstracts, titles, and keywords in a systematic literature review. It is challenging to replicate Google Scholar’s searches as well because of lacking stability over time. However, in this subject, Google Scholar is not entirely excluded. In determining the type of literature, we use Google Scholar as a pre-survey database to help authors choose the classification’s general categories. IEEE Xplore was excluded in this review because it provides articles that focus on computer science.

Research selection included searching for academic articles and then conducting three rounds of filtering screening. All irrelevant articles were deleted in the first filter. The second round is to scan headlines and abstractions to remove duplicate and unrelated articles. In the last iteration, the full article filtered out of the second iteration was carefully reviewed. In the database used to locate the key of the article, to identify Framing theory research, we use the contains “Framing theory,” “framing,” a mixture of different variants, such as “framing analysis” keyword, “OR” and “AND” and “operator” and “public relations” together. The specific query process is shown in Figure 1.

We set the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria as follows. Inclusion criteria are:

(i) The articles should focus on public relations studies and be classified with taxonomy method (Alaa et al., 2017) depending on authors’ preferred style, which include three main categories: review and survey articles, application articles and future implications articles;

(ii) The publication must be a scholarly article, conference paper, or conference proceeding; and

(iii) The publication date must be within the range from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019.

The exclusion criteria are: (i) non-English; (ii) Publication with words like ‘framing’ and ‘public relations related aspect’ in the abstract but does not include the two as its research objectives or research methodology, or publication. The two words are used irrelevantly.

Statistical Information Results

The first-round review resulted in 522 papers: 177 from the WoS, 190 from Proquest Central, and 150 from Scopus. Among them, have twenty-two duplicates. After reviewing abstracts and titles, articles were further excluded, with a total number of 365 left. The number of remaining papers with both “Framing theory” or “framing” and “public relations” in their titles, abstracts, or keywords was 135. However, this did not ensure that all of these papers would be useful for this review because these words may not have been related to each other in these studies, or they may not have been a part of the research objectives or methods. They may have been just individual words that happened to be included in the paper or referred to as a part of the research background. Eighty-five papers were picked in the final set, all of which were related to Framing theory application in public relations through different topics. However, concerning the inclusion criteria set previously, eighty-five papers on communication, public relations, and sociology were divided into three categories. The classification method is shown in Figure 2 is used to review the mainstream research of Framing theory and its general application in public relations. The first category includes review articles related to the application of Framing theory (3/85 papers). The second category is related to application articles (81/85). The third category includes implication articles (1/85 papers). The categories are shown below.

Review Article

This paper summarizes Framing theory’s application in public relations. One study involved how public relations researchers understand Framing theory (Crow & Lawlor, 2016). Another involves how the media frame describes public relations practitioners (Dustin, 2008). The last study summarizes the communication frame’s value in corporate communication strategies (Zerfass & Volk, 2018).

Studies Conducted on the Application

This section reviews the application of Framing theory in the field of public relations. The articles are divided into different topics, and the selected works are divided into several categories.

Model Development and Application based on Framing theory: One category comprises models developed based on Framing theory, which can be used in public relations. Under this category, the narrative policy framework model (NPF) can explain the policy process (Jones, 2018). In public relations practice, through observing the correlations between the specific media frame and the individual frame, an evaluation model was established, which could be used in public relations practice to prepare online news releases and manage organizational image and reputation through media (Jakopovic, 2017). From the perspective of theoretical considerations, the structural equation model was used to assist companies with advancing CSR communication efforts (Bhalla & Overton, 2019).

Application of Framing Theory: This part reviews the applications of framing analysis and its type in public relations. Selected papers were classified depending on the Framing theory applications in a specific aspect of public relations.

Framing Analysis in Public Relations Activities: This part will summarize the application of Framing theory in three major public relations activities. The three main public relations activities are communication strategy, crisis response, and reputation management.

Strategic Communication: The research of strategic communication in public relations, the work under this category, summarizes Framing theory’s application in communication effectiveness of public relations information. The review will describe the Framing theory’s application from five aspects: media relations, public health information dissemination, corporate social responsibility communication, public relations strategy, and public diplomacy. Based on media relations, the literature discusses controlled media relations, for example, “media frames used to generate interest provide insight into strategies for influencing behavior through a controlled form of media relations” (Holladay & Coombs, 2013, p. 101); The relationship between media practitioners, such as the frame analysis of media reports, aims to describe media practitioners’ views on national public relations policies (Sterne, 2010); Media relations in lobbying strategies, such as using the reporting frames as a control variable to test the impact of media attention on the advocacy process of interest groups (Debruycker, 2018). Based on public health information dissemination, for example, how to frame information for low-income people to achieve more effective communication (Debruycker, 2018) and thematic framing analysis the organization’s email messages to facilitate a more effective fundraising effort (Weberling, 2012).

Based on CSR communication, Framing theory was used to develop and test a model (Chung & Lee, 2019). To understand how private interest groups use public art in public relations strategies Framing theory was applied to media reports (Chambers & Baines, 2015). It discusses how stakeholders conduct strategic communication using the analysis of news frame theme. Based on public diplomacy, several articles have studied the misinterpretation of national foreign policy by the public due to the lack of the function of public information frames (Shenhav et al., 2010); clarifying the impact of the column frame topic on a country’s public opinion and foreign policy (Golan & Carroll, 2012). Framing theory was used as a tool of political discourse analysis to study the role of media diplomacy in public diplomacy strategies (AzpÃroz, 2013). The thematic classification of public foreign policy information was carried out to explore which topics prevail in actual national decision-making (Labonté & Gagnon, 2010). A thematic analysis of news reports on international relations events was conducted to understand the impact of government policies and public opinion on the news frames (Bureet, 2015).

Public Relations Crisis: This category’s work summarizes Framing theory in researching the public relations crisis for public relations crisis research. Papers were summarized from crisis communication, crisis coping strategies, crisis attributes, and public attitudes. Based on crisis communication, relevant literature includes a news presentation framework, such as framing analysis of public relations personnel’s statements in a crisis to assess the impact of emotional and rational frameworks on crisis communication information (Claeys et al., 2013); Comment frames, such as those that were framing comments on social media to help organizations understand citizens’ perceive crises (Tampere et al., 2016); A media coverage frames, such as an analysis of media coverage in a crisis, focus on a textual element of the crisis communication process or how media politicizes the crisis (Park et al., 2016). Framing theory was also used to discuss the linguistic impact of “labels” in media reporting (Appelman & Asmara, 2018). Based on the crisis response strategy and the perspective of enterprise strategy, this paper conducts a framing analysis of stakeholders’ comments. The research shows that the proactive framework can produce more positive effects (Appelman & Asmara, 2018). Based on crisis attributes and public attitudes, Framing theory was used to examine how the perceived locus of crisis cause (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015) and the impact of the theme frames on public relations practitioners and journalists (Yan & Kim, 2015).

Reputation Management: This category’s work summarizes Framing theory in researching reputation management of public relations. The Framing theory application will be summarized from two aspects: national-regional reputation and corporate reputation. Based on national-regional reputation, relevant literature is presented from the perspective of media content framing analysis. For example, Framing theory is used to analyze how the cultural framework in Canadian media reports has influenced the Canadian public’s perception of China and Chinese immigrants (Chen & Gunster, 2018) and how mainstream European publications frame Beijing’s image (Xu & Cao, 2018). Based on corporate reputation, relevant literature often links corporate reputation with corporate social responsibility. For example, framing the materials (media reports, organization websites, sustainability reports) related to an enterprise’s human resource management plan, to explore how corporate portrays its aging workforce initiative (Park et al., 2016); Framing theory can be used to explain the potential effects of CSR communication, and the company can better deal with negative publicity and protect its reputation (Chung & Lee, 2019). Framing the state media’s portrayal of corporate social responsibility to help companies decide how to conduct their business to enhance their reputation (Tang, 2012), is an example.

Frame Types in Public Relations

This section reviews the application of different frames in public relations, including visual and textual frames.

Visual Frame: In the study of public relations’ visual frames of public relations, how visual information influences public relations efforts, especially when giving voice to silent interests. For example, the visual framing of Picasso’s famous painting Guernica, which took him just over three weeks to create, this paper and its relevance to public relations aims to examine how a military event can be framed by visual communication (Xifra & Heath, 2018); For example, framing the campaign advertisements during the political election in Australia, these advertisements content were examined as cultural texts to explore the stance of these politicians (Milner, 2012); The framing analysis of the photos of detainees in U.S. naval base is an example, showing that discourse can be constructed through non-linguistic practice rather than linguistic practice (Veeren, 2011).

Text Frame: In the study of the text frame of public relations, this category’s work summarizes the Framing theory’s application in analyzing the text frame of public relations. The overview will describe the Framing theory’s application from four aspects: media report text, social media platform text, public relations material text, and magazine text. Based on media reports, Framing theory examines how the media under different ideologies report social events. For example, the coverage frames are interpreted with ideological differences. To explore the reasons for differences and theoretical implications (Xu & Cao, 2018); Framing theory was applied to represent different ideological views, such as the function of their locations (Molloy, 2015). The Framing theory was used to explore how media in different countries covered the same event and offers insights into opportunities and obstacles of media reporting for public initiatives (Khakimova et al., 2014).

Framing theory was also used to analyze interdependency between media systems and political systems interprets how propaganda influences on the media particularly when the global issue involving their home countries, and examines the coverage context of politician’s remarks, noting that the frames presented in the media are greatly influenced by political elites (Betts & Krayem, 2019). Besides, Framing theory was applied to examine how the media framed the discourse regarding politician, using the frame analysis to explore the overall media discourse about the politician who manipulated public opinion during the election (Kluknavská, 2015) or to explore what role does the state media play in shaping public opinion (Lan, 2017). Framing theory could also analyze the frame competition in public relations, showing which voices and frames dominate the debate (Wood, 2017).

Based on Framing theory, an experiment was conducted to examine the impact of different types of CSR-framed news on recipients’ product purchasing intentions (Sikorski & Müller, 2018). Specific framing was used to uncover how particular communist legacies in specific contests create public enemies who lose sympathy and support from the public (Jakopovic, 2017). One article draws on Framing theory to understand the actors, topics or issues, and coverage frames used in media during the election period (Matingwina, 2019). One paper showed how a crisis in the current public healthcare system is presented by various framing devices (Lewis et al., 2017). Based on the research of social media content, the review involves two aspects. One is the politicians’ social media tweets: the study explored how legislators manage their fan pages on Facebook to understand how politicians manage public relations through social media; the other one is social media comment. Framing theory was used to analyze public comments, helping to understand the keyframing approaches (Shelton et al., 2016). Based on public relations materials, Framing theory was used to explore how political actors frame issues by observing framing behavior and what it reveals about each side’s political strategy (Mucciaroni, 2011). By analyzing and comparing frames in public relations materials with those in the third party and newspaper coverage, the study will determine the political leader’s effectiveness to influence others to utilize his frames. Cury, (2017) article use framing analysis of documents produced by an organization to explore how they are constructed by the policy context. Lancaster et al. (2011) explore how the media define the public interest by emphasizing specific frames and construct public discourse to influence political decisions. Based on magazine text, Framing theory was adopted to study framing devices to reveal the discursive tensions of celebrity (Hopkins, 2017) to examine the diversity of framing over the past decade by public relations publications (Austin, 2010).

Stakeholder Relations

This section reviews the application of Framing theory to different stakeholder relations in public relations. One paper applying Framing theory examined how the media defined the organization and built its frames into public discourse (Cabosky, 2014). Based on corporate-media relations, Framing theory was applied to understand how corporate earnings press are reframed into financial news by investigating whether the company conducted frames are adopted or reframed by news agencies (Cabosky, 2014). Similarly, organization-journalist relations, Framing theory was applied to examine to what degree can action performed by inter-governmental bodies could affect the media’s content (Rettig & Avraham, 2015). In relation to PR practitioners-journalists relations, Framing theory was used to provoke a discussion about the role of silence and invisibility in public relations (Rettig & Avraham, 2015). A study conducted framing analysis to understand how journalists framed PR professionals’ occupational role and job performance (Lambert, 2018). Based on the implications of future application of “Framing theory” in PR, Anderson (2018) article seeks to introduce the counter-framing concept to public relations to help scholars examine the democratic environment accurately where competitive debate is excepted.

Components Results

After content summarizing samples, data were reviewed and arranged according to the studies’ different components such as research types, research objectives, and research methods. Inductive methods are adopted in analyzing the results because no hypothesis or speculation had been set before the literature review.

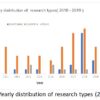

Figure 3 shows the annual distribution trend of study types for these studies. There are two findings here. First, in the past decade, relevant research has not always shown an upward trend. It has been fluctuating for many years. However, in 2018, it peaked in number, and in 2019, this number fell again. The second finding shows that the number of qualitative research papers each year exceeds the quantitative research in this field.

The next aspect being examined is the distribution of research objectives over the ten years. According to the primary goals of public relations research, they can be classified as follows: action planning to carry out sports with specific purposes and intent; evaluation to measure the effectiveness of public relations-related work; communication to pass public relations-related information; strategies to act as part of the overall strategic function management of the organization. In Figure 4, the research objectives of these samples are listed in columns. There are 20 articles about action planning, 20 articles about evaluation, 35 articles related to communication, and only ten articles refer to strategies. This shows most studies within the last ten years focus on public relations communication, which focuses on the frame. Few are taking the strategic study, which means a limited epistemological approach was used to explore how Framing theory was applied in public relations. However, some efforts are being made to explore new perspectives, such as studies of the vertical application of multiple public relations frames.

Framing theory was applied in an interdisciplinary field with no unified methods. It borrows tools from other sources. In these samples, diverse research methods are employed, setting examples for other researchers to plan future studies by importing tools from fields such as sociology, psychology, linguistics, or rhetoric. Most studies were conducted with content analysis. Besides content analysis, the articles’ methods over the last ten years include discourse analysis, thematic analysis, textual analysis, experimental study, interview analysis, ethnographic study, and focus group study. However, in 3 out of the 85 samples, the researchers conducted the study with a literature review approach to describe a specific aspect of framing analysis in public relations.

Discussion

This review introduces the most relevant studies on Framing theory applications in public relations. The purpose is to reveal the research trends in this field. It is a comprehensive one, focusing on Framing theory applications rather than framing analysis in the field of public relations. A taxonomy method, conducted in the systematic literature review, can benefit this research from two perspectives. On the one hand, a taxonomy of literature will help a new researcher grab the whole picture who studies Framing theory applications in public relations. On the other hand, it helps to classify previous studies into a meaningful and manageable layout.

Although framing theoretically exists everywhere and framing analysis applies to many different kinds of texts, this systematic literature review indicates that compared with large numbers of academic articles, including journal papers and conference papers within the last decade, most of the Framing theory related works in public relations focus on stakeholder content (what frame), and there are few publications on frame effects (locus of effect). In addition to this, there is little research on the frame-building process (how framing). Another problem revealed in this systematic literature review is that as the years pass, there is no trend showing that researchers could reflect and reconsider the fundamental rules in Framing theory because the number of empirical studies always far surpasses that of theoretical studies.

Statistical data on the research components of articles identify Framing theory application in public relations areas. The survey conducted revealed aspects with research status quo, research gaps, and research implications.

The Status Quo of Studies

The systematic literature review identified two general characteristics of Framing theory’s current application in public relations studies. First, because of different understandings of framing, researchers attach more attention to research with framing analysis as a tool without solving the epistemological problem of the term ‘framing.’ While most of the studies on framing tend to analyze the existence of frames in various text, little research has examined the sources and reasons behind the frame creation and dissemination, especially the ideological and cultural differences. Second, scholars have put forward several framing models and theoretical perspectives over the past decade, predicting and explaining key relationships, crisis response, and reputation management functions of public relations. However, the positive side is the additional attention paid to empirical research in public relations framework research. Some researchers borrow tools from other approaches or subjects and create more diversified research methods. Also, research subjects are moving from a single frame to multiple frames.

Gaps in Recent Research and Research Implications

In the following section, gaps in recent Framing theory application in public relations studies are elaborated, and recommendations for such intervals based upon Framing theory are proposed. Specifically, the gaps between theory and practice and the gaps in research methods and objectives are illustrated.

Gaps Between Longitudinal and Horizontal Research: The results show that in public relations practice, the concepts of framing, information subsidies, and agenda-setting were combined to explore frameworks of stakeholder relations through a timeline reviewing the literature. And then move to stakeholder frame analysis. After that, the studies turned the framing lens inward upon practitioners’ discourse and how it was framed diversely over the last decade. Fortunately, over the past decade, public relations scholars started to shift their focus from a single frame to a competitive frame, considering the impact of multiple frames exert an influence on an individual’s perceptions and attitudes. However, these studies remain at the horizontal studies level, focusing on frames used in organizational communication to the public rather than how it was framed.

Proposition: The study of public relations through framing can optimize public relations scholarship itself and contribute to Framing theory’s theoretical context. Thus, the study of public relations via framing is to approach the frame with more theoretical rigor. We need to determine the selected frames and salient them. Besides, we also need to pay attention to who constructs the frames, what purpose they are constructed, what social context they are constructed, and their effect on the public. That is the way to conduct longitudinal framing research.

Gaps in Research Methods: Researchers’ gaps in their understanding and application of research methods in the public relations framing studies are shown in the literature review. Some researchers engaged in highly academic attempts by combining framing analysis with tools from other fields or exploring new methods. Although this has developed different research methods for the Framing theory application in public relations, according to the statistical data of research methods, 49.4% of the research focuses on qualitative or quantitative content analysis. This result still shows the monotony of the research methods used by scholars. Furthermore, only 9.4% of studies among the examined articles use the mixed method. The result is the same as statistics from 1990 to 2009.

Proposition: Framing theory is a very promising paradigm for examining public policy, information, and public response, but it is still a fractured paradigm, without a coherent, holistic definition (Hallahan, 1999), and public relations study is an interdisciplinary subject. This combination engenders diversities as well as challenges. Besides content analysis, researchers have more possibilities to explore in methodology such as fieldwork and so on. Researchers could use more mixed research methods to enrich the dimension of research methods, enhancing the research’s reliability and validity.

Gaps in Research Objectives: Another noticeable gap lies in the uneven distribution of the objectives of these studies. Even though framing is recognized as existing everywhere around us, current research primarily analyzes frame information in public relations texts. Statistical data analysis shows that 41.1% of the articles’ research goal is to analyze which frame themes exist in the public relations text. In comparison, strategic research accounted for only 11.7% of the total. Action planning research and evaluation research account for 23.5%, respectively. No matter why public relations studies with the application of Framing theory could hardly meet the demands of public relations markets.

Proposition: Public relations are defined as balancing organizations and the public’s interests by managing stakeholders’ relationships. The practice of public relations is designed to manage relationships and support communication strategy goals. For example, in the study of public relations crisis, the researchers interested in what frame was adopted by media rather than how crisis-hit organization responds to it; that is to say, the researcher does not pay special attention to how to measure the effectiveness of the strategy of public relations crisis, thus hard to provide actionable guidance and strategy suggestions for the future public relations practice. Based on the findings in this review of previous studies, scholars should pay more attention to action planning objectives and strategies to make public relations research gain more practical guiding significance.

Conclusion

This paper has carried out a systematic literature review by surveying and taxonomizing related works in Framing theory application in public relations studies during the last decade (from 1st of January 2010 to 31st of December 2019). While previous systematic literature reviews have mostly been carried out in the healthcare field with quantitative synthesis, considering the character of public relations studies, a descriptive qualitative synthesis has been provided without a meta-analysis. This study aims to do a holistic, systematic review over the last ten years of all the related research on Framing theory application in public relations studies with taxonomic description, research trends, research status quo, and gaps, which provides a better development for further studies.

The review findings indicate that framing plays a vital role in public relations. It was used to measure attitudes and behavioral intentions and proposed several models of framing that could be applied to this research area. There is triple nature of framing application in public relations research: frames in organizations, frames in media, and frames in public. Because of the interdisciplinary nature of public relations, the research closely related to sociology has examined the frame function; research closely related to psychology has examined framing effects. Research closely associated with mass communication has examined framing themes. Although the past decade’s research trend has shifted to focus on the frame’s competition in public relations, the relevant research remains at the horizontal level. As Chong and Druckman (2007) point out, “little is known about the dynamics of framing in competitive contexts.” The longitudinal exploration of Framing theory application could help scholars understand the dynamics of framing in public relations.

However, since a systematic literature review can only maintain minimal bias, this research is no exception. It has some limitations. First, the study detected setbacks in Framing theory application in public relations studies through statistical analysis. Still, it failed to explain why, because individual systematic literature reviews are more suited to discovering problems than finding ways to solve them. Second, a review of papers published within the last decade is not sufficient for identifying the evolution of Framing theory application in public relations studies because Framing theory has been used over a much longer period. To gain a full view of this theory’s development, reviews should employ a more comprehensive time range. The third limitation lies in that a rigorous and comprehensive study of papers published in English has been conducted, whereas papers published in other languages are not included.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the Ph.D. research committee, who have contributed to this research as a whole.

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reference

Alaa, M., Zaidan, A. A., Zaidan, B. B., Talal, M., & Kiah, M. L. M. (2017). A review of smart home applications based on the Internet of Things. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 97, 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2017.08.017

Anderson, W. B. (2018a). Counter-framing: Implications for public relations. Public Relations Inquiry, 7(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147×18770229

Anderson, W. B. (2018b). Counter-framing: Implications for public relations. Public Relations Inquiry, 7(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147×18770229

Appelman, A., & Asmara, M. (2018a). A crisis by any other name? Examining the effects of journalistic “crisis labeling” on corporate perceptions. Newspaper Research Journal, 39(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532918761060

Appelman, A., & Asmara, M. (2018b). A crisis by any other name? Examining the effects of journalistic “crisis labeling” on corporate perceptions. Newspaper Research Journal, 39(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532918761060

Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2015). Framing theory in communication research. Origins, development, and current situation in Spain. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 423–450. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2015-1053en

Austin, L. L. (2010). Framing diversity: A qualitative content analysis of public relations industry publications. Public Relations Review, 36(3), 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.04.008

AzpÃroz, M. L. (2013, April 4). Framing as a Tool for Mediatic Diplomacy Analysis: Study of George W. Bush’s Political Discourse in the “War on Terror” by MarÃa Luisa AzpÃroz :: SSRN. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3172300

Bartholomé, G., Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. (2017). Towards A Typology of Conflict Frames. Journalism Studies, 19(12), 1689–1711. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2017.1299033

Betts, J., & Krayem, M. (2019). Strategic Othering: Framing Lebanese Migration and Fraser’s “Mistake.” Australian Journal of Politics & History, 65(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12538

Bhalla, N., & Overton, H. K. (2019). Examining cultural impacts on consumers’ environmental CSR outcomes. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 24(3), 569–592. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccij-09-2018-0094

Borah, P. (2011a). Conceptual Issues in Framing Theory: A Systematic Examination of a Decade’s Literature. Journal of Communication, 61(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x

Borah, P. (2011b). Conceptual Issues in Framing theory: A Systematic Examination of a Decade’s Literature. Journal of Communication, 61(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x

Burrett, T. (2015, February 10). National Interests Versus National Pride. Taylor& Francis Online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/PPC1075-8216610502?journalCode=mppc20

Cabosky, J. M. (2014a). Framing an LGBT organization and a movement: A critical qualitative analysis of GLAAD’S media releases. Public Relations Inquiry, 3(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147×13519638

Cabosky, J. M. (2014b). Framing an LGBT organization and a movement: A critical qualitative analysis of GLAAD’S media releases. Public Relations Inquiry, 3(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147×13519638

Chambers, D., & Baines, D. (2015). A gift to the community? Public relations, public art, and the news media. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(6), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415572323

Chen, S., & Gunster, S. (2018). China as janus: the framing of China by British Columbia’s alternative public sphere. Chinese Journal of Communication, 12(4), 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2018.1530686

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007a). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007b). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Chung, A., & Lee, K. B. (2019a). Corporate Apology After Bad Publicity: A Dual-Process Model of CSR Fit and CSR History on Purchase Intention and Negative Word of Mouth. International Journal of Business Communication, 232948841881913. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488418819133

Chung, A., & Lee, K. B. (2019b). Corporate Apology After Bad Publicity: A Dual-Process Model of CSR Fit and CSR History on Purchase Intention and Negative Word of Mouth. International Journal of Business Communication, 232948841881913. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488418819133

Claeys, A. S., Cauberghe, V., & Leysen, J. (2013). Implications of Stealing Thunder for the Impact of Expressing Emotions in Organizational Crisis Communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(3), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2013.806991

Crow, D. A., & Lawlor, A. (2016). Media in the Policy Process: Using Framing and Narratives to Understand Policy Influences. Review of Policy Research, 33(5), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12187

Cury, E. (2017). Muslim American Policy Advocacy and the Palestinian Israeli Conflict: Claims-making and the Pursuit of Group Rights. Politics and Religion, 10(2), 417–439. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755048317000062

Debruycker, I. (2018a). Blessing or Curse for Advocacy? How News Media Attention Helps Advocacy Groups to Achieve Their Policy Goals. Political Communication, 36(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1493007

Debruycker, I. (2018b). Blessing or Curse for Advocacy? How News Media Attention Helps Advocacy Groups to Achieve Their Policy Goals. Political Communication, 36(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1493007

Durach, C. F., Kembro, J., & Wieland, A. (2017a). A New Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 53(4), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12145

Durach, C. F., Kembro, J., & Wieland, A. (2017b). A New Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 53(4), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12145

Dustin W, D. (2008, May 8). Maximizing Media Relations Through a Better Understanding of the Public Relations – Journalist Relationship. MIAMI. http://www.bu.edu/comtalk/files/2012/11/Maximizing-Media-Relations.pdf

Eden, J. (2011). Finding What Works in Health Care Standards for Systematic Reviews (1st ed.). National Academies Press.

Entman, R. M. (1993a). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Gamson, W. A., Croteau, D., Hoynes, W., & Sasson, T. (1992). Media Images and the Social Construction of Reality. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 373–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.002105

Gitlin, T. (2003). The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left, With a New Preface (First Edition, With a New Preface ed.). University of California Press.

Golan, G. J., & Carroll, T. R. (2012). The op-ed as a strategic tool of public diplomacy: Framing of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. Public Relations Review, 38(4), 630–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.06.005

Gonzalez, C., Dana, J., Koshino, H., & Just, M. (2005). The framing effect and risky decisions: Examining cognitive functions with fMRI. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2004.08.004

Hallahan, K. (1999). Seven Models of Framing: Implications for Public Relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11(3), 205–242. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1103_02

Hertog, J. K., & McLeod, D. M.. (2001). A Multiperspectival Approach to Framing Analysis: A Field Guide (1st ed., Vol. 3). Routledge.

Higgins, J., López-López, J. A., Becker, B. J., Davies, S. R., Dawson, S., Grimshaw, J. M., McGuinness, L. A., Moore, T. H. M., Rehfuess, E. A., Thomas, J., & Caldwell, D. M. (2019). Synthesising quantitative evidence in systematic reviews of complex health interventions. BMJ Global Health, 4(Suppl 1), e000858. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000858

Holladay, S. J., & Coombs, W. T. (2013). The great automobile race of 1908 as a public relations phenomenon: Lessons from the past. Public Relations Review, 39(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.12.002

Hopkins, S. (2017). UN celebrity ‘It’ girls as public relations-ised humanitarianism. International Communication Gazette, 80(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048517727223

Jakopovic, H. (2017a). Predicting the Strength of Online News Frames. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 15(3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.15.3.5

Jakopovic, H. (2017b). Predicting the Strength of Online News Frames. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 15(3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.15.3.5

Jones, M. D. (2018). Advancing the Narrative Policy Framework? The Musings of a Potentially Unreliable Narrator. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 724–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12296

Khakimova, L., Madden, S. L., & Liu, B. F. (2014). The death of bin Laden: How Russian and U.S. media frame counterterrorism. Public Relations Review, 40(3), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.01.009

Kluknavská, A. (2015). A right-wing extremist or people’s protector? Media coverage of extreme-right leader Marian Kotleba in 2013 regional elections in Slovakia. Intersections, 1(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v1i1.35

Labonté, R., & Gagnon, M. L. (2010). Framing health and foreign policy: lessons for global health diplomacy. Globalization and Health, 6(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-6-14

Lambert, C. A. (2018). A media framing analysis of a U.S. presidential advisor: Alternative flacks. Public Relations Review, 44(5), 724–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.07.006

Lan, X. (2017). Does money talk? A framing analysis of the Chinese Government’s strategic communications in the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Chinese Journal of Communication, 11(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2017.1375534

Lancaster, K., Hughes, C. E., & Spicert, B. (2010). Illicit drugs and the media: Models of media effects for use in drug policy research. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(4), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00239.x

Lewis, S., Collyer, F., Willis, K., Harley, K., Marcus, K., Calnan, M., & Gabe, J. (2017). Healthcare in the news media: The privileging of private over public. Journal of Sociology, 54(4), 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317733324

Lim, J., & Jones, L. (2010). A baseline summary of framing research in public relations from 1990 to 2009. Public Relations Review, 36(3), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.05.003

Loan, V. (2020). The way public relations practitioners influence media agendas in Vietnam. HCMCOUJS – ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, 5(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.46223/hcmcoujs.econ.en.5.1.76.2015

Matingwina, S. (2019). Partisan Media in a Politically Charged Zimbabwe: Public and Private Media Framing of 2018 Elections. African Journalism Studies, 40(2), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2019.1654534

Milner, L. (2012). Moving forward with an action plan: Political campaigning on the big screen. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 6(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1386/sac.6.2.125_1

Molloy, D. (2015). Framing the IRA: beyond agenda setting and framing towards a model accounting for audience influence. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 8(3), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2015.1096654

Mucciaroni, G. (2011). Are Debates about “Morality Policy” Really about Morality? Framing Opposition to Gay and Lesbian Rights. Policy Studies Journal, 39(2), 187–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00404.x

Mulrow, C. D. (1987). The Medical Review Article: State of the Science. Annals of Internal Medicine, 106(3), 485. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-485

Nelson, D. J. (2019, June 24). OPUS at UTS: Framing the carbon tax in Australia : an investigation of frame sponsorship and organisational influence behind media agendas – Open Publications of UTS Scholars. OPUS. https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/134120

Park, S., Bier, L. M., & Palenchar, M. J. (2016a). Framing a mystery: Information subsidies and media coverage of Malaysia airlines flight 370. Public Relations Review, 42(4), 654–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.06.004

Park, S., Bier, L. M., & Palenchar, M. J. (2016b). Framing a mystery: Information subsidies and media coverage of Malaysia airlines flight 370. Public Relations Review, 42(4), 654–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.06.004

Rettig, E., & Avraham, E. (2015a). The Role of Intergovernmental Organizations in the “Battle over Framing.” The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(1), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215613060

Rettig, E., & Avraham, E. (2015b). The Role of Intergovernmental Organizations in the “Battle over Framing.” The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(1), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215613060

Sahni, S., & Sinha, C. (2016). Systematic Literature Review on Narratives in Organizations: Research Issues and Avenues for Future Research. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 20(4), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262916678085

Sarantakos, S. (1998). Social Research (2Rev Ed). Palgrave Macmillan.

Scheufele, B. (2004a). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications, 29(4), 401–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.29.4.401

Scheufele, B. (2004b). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications, 29(4), 401–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.29.4.401

Scheufele, B. (2004c). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications, 29(4), 401–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.29.4.401

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02784.x

Shelton, R. C., Colgrove, J., Lee, G., Truong, M., & Wingood, G. M. (2016). Message framing in the context of the national menu-labelling policy: a comparison of public health and private industry interests. Public Health Nutrition, 20(5), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980016003025

Shenhav, Sheafer, & Gabay. (2010). Incoherent Narrator: Israeli Public Diplomacy During the Disengagement and the Elections in the Palestinian Authority. Israel Studies, 15(3), 143. https://doi.org/10.2979/isr.2010.15.3.143

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019a). How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019b). How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Sikorski, C., & Müller, L. (2018). When Corporate Social Responsibility Messages Enter the News: Examining the Effects of CSR-Framed News on Product Purchasing Intentions and the Mediating Role of Company and Product Attitudes. Communication Research Reports, 35(4), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2018.1506757

Sterne, G. D. (2010). Media perceptions of public relations in New Zealand. Journal of Communication Management, 14(1), 4–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632541011017780

Tampere, P., Tampere, K., & Luoma-Aho, V. (2016). Facebook discussion of a crisis: authority communication and its relationship to citizens. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(4), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccij-08-2015-0049

Tang, L. (2012). Media discourse of corporate social responsibility in China: a content analysis of newspapers. Asian Journal of Communication, 22(3), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2012.662515

Veeren, E.V. (2010). Captured by the camera’s eye: Guantánamo and the shifting frame of the Global War on Terror. Review of International Studies, 37(4), 1721–1749. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210510001208

Vilma, L. (2015). Understanding Stakeholder Engagement : Faith-holders, Hateholders & Fakeholders. Research Journal of the Insitute for Public Relations, 2(1), 17–18. https://instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/updated-vilma-pdf.pdf

Wang, L. (2020). [PDF] A systematic literature review of narrative analysis in recent translation studies | Semantic Scholar. SEMANTIC SCHOLAR. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-systematic-literature-review-of-narrative-in-Wang-Ang/81c7a6de8d3bc9bbbb12dacb8ca5ac297bd409c6

Weberling, B. (2012). Framing breast cancer: Building an agenda through online advocacy and fundraising. Public Relations Review, 38(1), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.08.009

Wood, T. (2017). The many voices of business: Framing the Keystone pipeline in US and Canadian news. Journalism, 20(2), 292–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917717536

Xifra, J., & Heath, R. L. (2018). Publicizing atrocity and legitimizing outrage: Picasso’s Guernica. Public Relations Review, 44(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.10.006

Xu, J., & Cao, Y. (2018a). The image of Beijing in Europe: findings from The Times, Le Figaro, Der Spiegel from 2000 to 2015. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(3), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-018-0103-0

Xu, J., & Cao, Y. (2018b). The image of Beijing in Europe: findings from The Times, Le Figaro, Der Spiegel from 2000 to 2015. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(3), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-018-0103-0

Yan, Y., & Kim, Y. (2015). Framing the crisis by one’s seat: a comparative study of newspaper frames of the Asiana crash in the USA, Korea, and China. Asian Journal of Communication, 25(5), 486–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2014.990470

Zerfass, A., & Volk, S. C. (2018). How communication departments contribute to corporate success. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcom-12-2017-0146

Duan Kuan is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication (Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication) at Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. Her areas of academic interest are theoretical research in communication and public relations.

Nurul Ain Mohd Hasan (Ph.D., Massey University, New Zealand, 2013) is an Associate Professor of Communication in the Department of Communication (Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication) at Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. Her area of specialisation is corporate social responsibility in communication and public relations.

Julia WirzaMohd Zawawi (Ph.D., Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2017) is a senior Lecturer in the Department of Communication (Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication) at Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. She specializes in media studies, news framing, frameset, and experimental studies.

Zulhamri Abdullah (Ph.D., Cardiff University, 2006) is an Associate Professor of Corporate Communication in the Department of Communication (Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication) Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. He specializes in corporate communication and public relations.

Correspondence to: Nurul Ain Mohd Hasan, Department of Modern Languages and Mass Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed properly. The article may be reused without special permission provided that the original article is properly attributed. Reuse of an article does not imply prior approval by the authors or Media Watch.